Autumn where the sun rises in the windshield of the

west, a tangible hard glass frost erupting through our lips like chimneys as my

father and I locomotive down the dual arteries of Sherman and Moss avenue in

west Peoria, scrolling the news bulletins into black and white telescopes, an

fresh ink baton deposited in screen doors or mail slits or under beneath the

foamy lids of welcome matts. Morning in America, the smell of coffee pots

hissing and gargling—wisps of rich soil ferrying the scent of percolating

caffeine tickling the olfactory senses—the sounds of bacon and eggs slathered

in olive oil being sizzled and fried.

I have been a paperboy for a little over a year.

Things are happening on the scalp of the planet.

Nations smaller than the size of Delaware are being invaded. The united states is deploying air craft

carriers into the armpit of the Persian Gulf. There is tension and drama and

the threat of another Vietnam.

A war no one understands half the planet away where

fields of oil billow and churn in grisly exclamatory plumes.

Seemingly overnight signs have sprouted in front

lawn announcing WE SUPPORT OUR MEN AND WOMEN IN OPERATION DESERT Shield.

I read the headlines every morning before I slip the

heap of papers into the screen doors of patrons on my route so they can look at

the world affairs upon waking up and worry.

I am in

seventh grade and am playing two soccer

leagues, sprinting up and down the chalk geometry of the field . I arrive home

in the side of the station wagon, dollops of sweat lining my brow like drops of

tears.

I am still in my soccer garb. Once again when

Maurice arrives I am clad in my soccer uniform. My shin guards. Mom is wearing

her KISS THE COOK apron which apparently Maurice made a joke about when she

answered the door.

Mom has a smile on her face.

“David, Mr Alwaun has something he would like to ask

of you?” She says. She is looking at me

with her face tilted like a pinwheel in March.

Maurice asks me first how Soccer is going. He

smiles. I tell him fine.

Maurice holds out the insert that was in the paper a

couple of weeks ago, on Columbus day, the one with the Eiffel tower sprouting

from the center like an erection made

out of Legos.

“I was wondering if you’d like to represent this

district to win in a chance to win a trip to France.”

I’m astonished. I don’t know what to say. I look

down into the direction of my shin guards.

“I honestly think you earned it.” Maurice Alwaun

says, humbly, before commenting that I’ve done a superb performance, that he

has never had a complaint about me, that he honestly can’t think of a better

paper boy to nominate for the contest.

I look down. He says that I will have to glean

recommendations and prepare a speech in front of a bunch of judges but he

thinks I have as good of shot as any to win.

“France,” I say, looking down at my shin guards.”

France.

***

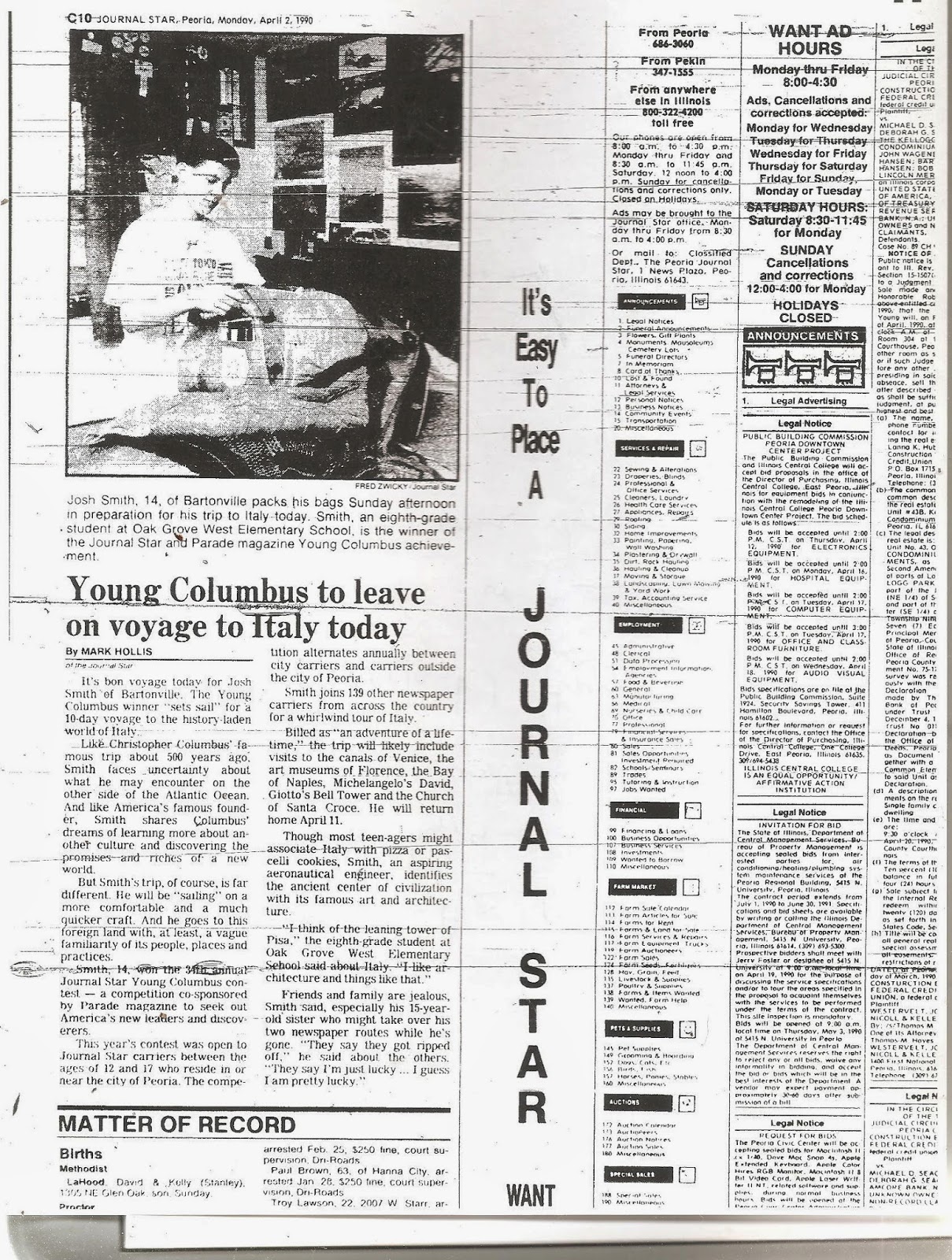

Mom calls up Josh

smith’s mother to inquire about the contest from last year. Smith’s mom said

that there was just no way that they ever could have imagined their son winning

the contest. There are things I need to do. I need to work on a speech. I need to get recommendations and references.

I find out Mario the Classroom bully is also in the contest. I try not to fathom what would happen if he would somehow win.

I need to pray.

***

Maurice is very forward with his recommendation,

stating that I am the best carrier he has in his district. This year is the

first year that there will be two winners from the Journal star. A winner from

the city and a winner from the county. Mom does the bulk of the soliciting. She calls up my soccer coach. We have old man Ricca who always paints me a card every Christmas and Myra McGann who are on my route. We ask Pastor Schudde. We ask my dad friend andy moore.

Everyone seemingly has confidence in me. everyone believes I will win.

Everyone seemingly has confidence in me. everyone believes I will win.

When I come home from school one day Mom asks to see me. She shows me a piece of paper with my sisters 3rd grade name on it.

On it is a personal essay she wrote about her brother who has a chance to go to France.

In the paper his eight year old sister says she is proud of him.

On it is a personal essay she wrote about her brother who has a chance to go to France.

In the paper his eight year old sister says she is proud of him.

Around the time I am nominated for the Young Columbus contest Superman, via a clod of ruby Kryptonite, loses his powers. He is pummeled by Lex Luther. He is jeered by Mxyzptlx. He is impotent. He is just another human being. He changes out of his outfit in an alley as to disguise himself.

For a month, Superman somehow lost the ability to fly.

For a month, Superman somehow lost the ability to fly.

***

I practice my speech. Josh Smith’s speech

started with a self-inflicted joke about his name correlating to his height. We

try to wedge a joke into my speech, the note cards pocketed in the side of my

pants—my hair coifed back in a slippery haze a la Pat Riley, trying to be

cultured—the main joke I have in my presentation comes when I endeavor to say

Merci beaucoup after having no French whatsoever licked into the last syllable,

the arched dashed of the lower case “p “ even visible in my stance.

I have rehearsed the

mechanics and intonations of my speech incessantly since Christmas. I have

given it to my family almost every night. Mother, composed the speech for me,

scribing it out in the long-hand cursive the looks like contorted balloons,

ethereal, capable of lifting off the blanket white of the page at any moments.

Mother speech evolves around the theme of Thanksgiving—having giving me a bible

passage where it talks about the fear of the lord blessing those who are

grateful in thanksgiving, the speech spills from my mouth in awkward syllables,

as it begins with me with an astute observation how it may seem weird now that

the holidays are over and everything, but for me this day is thanksgiving. The

speech, composed by the paper-thin fingers of my mother, her way of thanking

god for all of the blessings bestowed on her sub-middle class life, evinced

audibly through the lips of her 7th grade son, thick movie screen

glasses harnessing the distilled white of his forehead. I practice, knowing

that mom is bowed in the fashion of a thumb-sized pastel nativity figurine one

sole-knee reverence into the metaphysical direction of her individualized

living Jesus. I rehearse the speech of my mother, thanking her father in lieu

of arduous sojourn she herself has lived—thankful for the pangs that have

produced such wayward joys.

I practice my speech.

I look at my thirteen

year old body in the mirror, sculpt my hair as if the fibers are composed of

some sort of clay, the reflection looking back at me. In the side of my thick

glasses I can make out another diminutive reflection of my own pupil, a planetary

marble looking back at me every time I blink. It is as if I am never alone,

always scrutinizing myself.

The night before my

contest dad arrives home from work toting a good luck sign his fourth grade

class created, the Eiffel tower center limp, genuflecting slightly towards the

left hand side of the page, the words HELLO, PARIS, thickly carved in grade

school markers—each of his students sending me individual accolades, wishing me

good luck.

The night before as is

true with all the other nights, I pray. Pray, more than anything else, that I

may be granted something in this life to give me meaning, praying the way my father taught me to pray, genuflecting on the caps of my teenage knees asking the force above to give me something, to bless me, give me something tangible, something to color merit into my thirteen years of existence, begging, supplicating, praying, thinking of the Eiffel Tower asking God give me something, anything at all.

No comments:

Post a Comment